Do you look like your name? Research shows people can match names to faces of strangers

This suggests that stereotypes associated to names and faces can influence people in order to fit into society or live up to people’s expectations.

PRESS RELEASE: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Do you look like your name? Research shows people can match names to faces of strangers

People can match first names to faces of strangers with surprising accuracy, new research from HEC Paris reveals, and it may have something to do with cultural stereotypes we share within a society.

In an article published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, researchers conducted a series of experiments involving hundreds of participants in Israel and France. In each experiment, participants were shown a photograph of someone they had never seen before, and were asked to select the given name that corresponded to the face from a list of four or five names. Among those names was the unknown person’s real given name. In every experiment, the participants were significantly better (25 to 40 percent accurate) at matching the first name to the face than random chance (20 or 25 percent accurate depending on the experiment) even when ethnicity, age, name frequency and other socioeconomic variables were controlled for.

This suggests that stereotypes associated to names and faces can influence people in order to fit into society or live up to people’s expectations. They are culture-specific: a French Charlotte may look different from an American or a German Charlotte. And the French Charlotte is recognized as a Charlotte by French people, but not by non-French people.

In one experiment conducted with students in France and Israel, participants were given a mix of French and Israeli faces and names. French students were better than chance at matching French names to faces, but not at matching Israeli faces; and Israeli students were better at matching Israeli names to faces, but no better than chance at matching French faces.

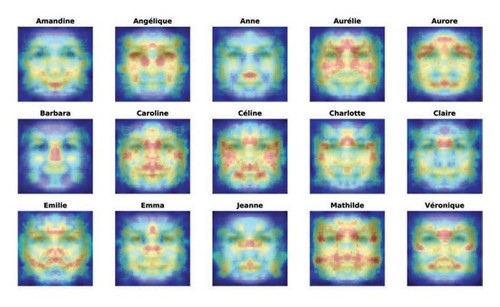

In another experiment, the researchers trained a computer, using a learning algorithm, to match names to faces. Using over 94,000 facial images, the computer was significantly more likely (54 to 64 percent accuracy) to be successful than random chance (50 percent accuracy). If a computer can accurately match a first name to a face, this suggests that the link resides in the face of the person, and not purely in the person perceiving that picture. Based on the computer accurate guesses, researchers were able to produce “heat maps”, showing for each name where the key areas for recognition of a name were on people’s faces on average.

The authors suggest that this manifestation of the name in a face is due to a self-fulfilling mechanism, such that people are motivated to alter their facial appearance to resemble the cultural stereotype associated with their name. This was supported by findings that show areas of the face that can be controlled by the individual, such as hairstyle, were sufficient to produce the effect.

The researchers showed that the effect disappears when people use an exclusive nickname instead of their given name. Thus, if the first name no longer has social value because it is not used, the motivation to look like the name’s stereotype disappears.

“These findings show that we all feel the pressure to live up to our name. We want to live up to society’s expectations; ultimately, we want to fit in,” says Professor Anne-Laure Sellier. “So when we meet someone we don't know, during recruitment or negotiations, for example, we have expectations based on how they look and since their face looks like a certain name, it is possible that we have expectations for a given face that are different from expectations for another.

“This research adds to considerable prior work showing that a large part of our evaluation of others is based on nonverbal cues. Our findings suggest that if we put our best face out there, part of it is our own essence, but another part of it is socially structured; it is shaped to please the group that we are motivated to belong to. We should be aware of this both in the workplace and society in general.”

/ENDS

For more information or to speak to Professor Sellier, please contact Stephanie Mullins at BlueSky PR on smullins@bluesky-pr.com or call +44 (0)1582 790 706.

Specializing in management education and research, HEC Paris offers a complete and unique range of educational programs for the leaders of tomorrow: Masters programs, Summer School, MBA, PhD, Executive MBA, TRIUM Global Executive MBA, open-enrolment and custom executive education programs.

Founded in 1881 by the Paris Chamber of Commerce and Industry, HEC Paris is a founding member of the Université Paris-Saclay. It boasts a faculty of 138 full-time professors, more than 4,400 students and over 8,000 managers and executives in training each year.

HEC Paris was ranked second business school in Europe by the Financial Times’ overall business school ranking in December 2016.

www.hec.edu

This press release was distributed by ResponseSource Press Release Wire on behalf of BlueSky Public Relations Ltd in the following categories: Men's Interest, Health, Women's Interest & Beauty, Business & Finance, Education & Human Resources, Media & Marketing, Public Sector, Third Sector & Legal, for more information visit https://pressreleasewire.responsesource.com/about.